A few years ago, a trusted literary friend suggested that I read a certain novel, which she likened to “adrenaline, hope, fear and pain mixed into one strange ocean, each feeling coming in waves.” In her emotional deluge, she forgot to mention the title of the book at first. It was none other than Everything Is Illuminated, the debut novel of Jonathan Safran Foer, the writer who would go on to produce the wildly popular 9/11 coming-of-age novel/picture book Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (now a major motion picture starring Tom Hanks).

In this post, I want to discuss Foer as a writer, largely in light of his premiere novel Everything Is Illuminated. As I see it, Foer belongs to a coterie of ‘literary’ authors, such as Colum McCann with his own 9/11 novel Let the Great World Spin and Haruki Murakami (in translation), who harness a dazzling array of formal conceits, precocious narrators, and sensational, often tear-jerking events to evoke “one strange ocean” of feelings in their readers. They engage in a writerly mode which Nigerian critic C. Namwali Serpell dubs “flippancy” for the way it keeps readers flipping through pages by treating grave issues (terrorist attacks, drug use, sexual liaisons) in a rather flippant manner, which is “intensely cathartic but ethically suspect.” I, for one, just call it sentimentality. From all the waves of feelings it forces me to feel, I can’t help but feel a little seasick because of it.

Let me get one thing straight from the start: I admire Foer’s writing. I really do. The same goes for McCann’s and Murakami’s. Foer’s best quality as a writer, and, indeed, what first drew the attention of his Princeton writing professor Joyce Carol Oates, is his sheer creative energy. Who would think to spin a tale about a three-hundred-year-old Jewish village AND have a one-sided correspondence between the author and a Ukrainian guy who writes in stilted English AND create a modern quest for a missing family lineage ALL in the same slim novel?

But then the moments of saccharine sensuality or pretentious philosophizing or hackneyed sentiments intervene. Let’s just look at one case example before we proceed. In the chapter “Falling in Love, 1791-1803,” which is among the worst sections for this kind of emotional button-pushing, we hear about the developing relationship between Yankel and the young foundling he is raising:

But more than that, no unloving words were ever spoken, and everything was held up as another small piece of proof that it can be this way, it doesn’t have to be that way; if there is no love in the world, we will make a new world, and we will give it heavy walls, and we will furnish it with soft red interiors, from the inside out, and give it a knocker the resonates like a diamond falling to a jeweler’s felt so that we should never hear it. Love me, because love doesn’t exist, and I have tried everything that does. (82)

Now, does any of that really make any sense? Starting with the incredibly vague bifurcation “it can be this way, it doesn’t have to be that way,” the cloying remarks slide from the third person into the first person plural with the declaration “we will make a new world,” which again comes off as a tad vague despite the nice ornamental imagery. A knocker that makes no sound? Wait, why? Then, the sequence culminates in the most non-sensical feature, a sudden, self-referentially incoherent imperative, implicitly directed at ‘you’ (the reader?), with a coy first person pronoun thrown into the mix. How are you meant to love if love doesn’t exist? And how has this conclusion been reached? And why the superfluity of absolute words, like “everything” and “never”?

I’ll tell you why—because it’s provocative and emotive. The book is talking to you after all. Foer performs a sly shift toward the reader with the turn of a pronoun or two, focusing first on Yankel’s love, then ‘our’ love, and finally ‘your’ love. The passage might be purposefully non-sensical to demonstrate something about the confusion of love, but then again, passages like this abound throughout the novel, leading me to think that such sentimentality is a stylistic choice rather than a singular demonstration of one character’s feelings. And this is what peeves me, or “spleens” me, to use the favorite word of the Ukrainian narrator, about Foer’s writing: it makes such creative and formal headway, only to puncture the vessel’s hull with this sappy, sentimental crap.

You can see why I take issue with it.

In the remainder of this post, though, I want to explore the formal devices that I find particularly inspiring and even illuminating in Foer’s first novel. Next, I will discuss the less savory features of Foer’s fiction in reference to what David Foster Wallace calls “cleveritis” in his famed 1993 interview with Larry McCaffery. Finally, I want to interpret one scene—in the chapter titled “Illumination”—which brings the strands of sentimentality and formal inventiveness together to illuminate something or another about contemporary fiction.

Talmudic Interpretations, Stilted English

The first thing to mention about Everything Is Illuminated (aside from the fact that Foer netted a record breaking $500,000 advance for this out-of-nowhere first novel) is its form. Two features stick out in particular.

The first is the threefold structure of the narrative, which consists of the recollections of Alexander Perchov (the Ukrainian narrator previously mentioned) concerning his time as translator and tour guide for one Jonathan Safran Foer (“an ingenious Jew” [3]), Jonathan’s reimagined family history based on his travels in Ukraine, and Alexander’s letters to Jonathan about their two developing narratives. As different as this novel is from Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, Foer’s second novel actually operates on a markedly similar threefold structure comprised of Oskar’s narrative, his grandfather’s letters to “my unborn son,” and his grandmother’s journals. An astute reader will notice even more similarities between the two seemingly disparate novels (writing, for example, seems to end up on all kinds of wonky surfaces in both novels: newsprint on babies, lipstick on ceilings, secret messages on trees, ink on hands, etc. etc.). Switching between diverse sub-narratives likely adds to the “flippancy” factor of Foer’s narrative by keeping things interesting. This is by no means limited to Foer’s fiction, of course. David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, for example, takes perspective switching up several more notches with its variety of styles and character arcs. The shame is that, in both of Foer’s novels, one of the sub-narratives is unbearably sentimental, crude, and a tad showy, as I will discuss in the subsequent section.

For now, though, I want to think about what makes the threefold structure of Everything Is Illuminated particularly compelling. First of all, each of the narratives builds off a different form of writing. Ostensibly, Alexander’s recollections are non-fiction narrative, as he describes his actual experience leading Jonathan across Ukraine. Meanwhile, Jonathan’s story is a fusion of historical fiction, building off his travels and facts about the war, and folklore, with its bizarre imaginings of life in the Trachimbrod shtetl from 1791 to 1941. The letters from Alexander, then, serve as an editorial commentary and interpretation of these narratives, not unlike the Jewish Talmud, which explicates the Hebrew scriptures. The point here is that portions of the text interpret and respond to each other in a way that unveils the uncertainties and creative jumps made in the writing process. In Alex’s first letter, for example, he calls out Jonathan for using “not truthful names” (25) for Ukrainian characters in his first chapter, while at the same time responding to Jonathan’s criticisms about using the word “Negroes” and even admitting that he lied about “how I am tall. I though it might appear superior if I was tall” (24). The criticism runs both ways, but it is also self-reflexive and unsolicited on Alex’s part. At other points, Alex questions the less believable or outright inane contrivances in Jonathan’s folktales, such as when he asks: “Why do women love you grandfather because of his dead arm?” (179). These letters thereby serve a highly redemptive purpose for the more sentimental parts of the narrative—the text points out some of its own crap, which lets the reader know that at least some of the crap is intentionally crappy.

As if the dialogue amid sub-narratives of the novel wasn’t enough, the summation of these sub-narratives also seems to be in dialogue with the writing process itself, specifically the process of writing fiction. It is, in effect, metafictional. The lynchpin of this novel’s metafiction comes in the inclusion of “Jonathan Safran Foer,” the novel’s author, as a character in the novel itself. From the start, the relation between fiction and non-fiction is thereby called into question: sure, this is a novel, but the author appears as a sort of avatar in the world he is creating. Moreover, Foer is drawing on real events, namely the Holocaust, and his own real-life trip to a shtetl called Trochenbrod, just a few vowels shy of the novel’s “Trachimbrod.” Within the novel, the Jonathan character also draws from “factual” documents within the world of the text, such as The Book of Past Occurrences which he nabs from an old Ukrainian lady—Jonathan includes a slightly altered excerpt about colorfully painted hands in one of his sections and renames the source text The Book of Antecedents. What we get, then, is a whole series of embellishments, inventions, edits and re-writings that looks something like this:

But it’s not just a mess. All of this fictionalization connects to one of the central thematic thrusts of the novel: the absolute loss of life and history perpetrated by the Holocaust and attempts to fill the lacunae and uncertainty left in the absence. Katrin Amian writes in a chapter on Foer’s novel that these “highly speculative narrative enterprises” serve to “reflect Jonathan’s genuinely creative—and unmistakably fictional—attempts to (re-)construct his family’s history and imagine what life my have been like for his Jewish-Ukrainian predecessors.” But this reconstruction, like any act of fiction, necessitates the creation of certain “not-truths,” as Alex remarks, “We are being very nomadic with the truth, yes? The both of us?” (179). The correspondence between the fictionalizing content of the novel—concerned as it is with reinvention of history—and the fictional form of the novel—with its manifold revisions, excerpts, and uncertainties—may justify lauding Everything Is Illuminated as a “brilliant” book, as several reviewers have.

This brings me to the second sparkling feature of Foer’s first novel, namely, its use of non-standard English, which occurs almost entirely in Alex’s sections. For the most part, Alex’s strange English consists of overwrought verbs (“manufacture” instead of make, “exhibit” instead of show, “masticate” for chew) and repetitive, thesaurus-sourced adjectives (“premium,” “petite,” “effervescent”), as well as a few odd constructions and not-quite-right phrases. Take, for example, the opening of Alex’s first letter:

I hanker for this letter to be good. Like you know, I am not first rate with English. In Russian my ideas are asserted abnormally well, but my second tongue is not so premium. I undertaked to input the things you counseled me to, and I fatigued the thesaurus you presented me, as you counseled me to, when my words appeared to petite, or not befitting. (23)

Much of the language is not grammatically incorrect per se (except for the occasional substitution of a highfalutin intransitive verb for a simple transitive one, as in “fatigued” for “worn out” in the passage above). Nor does it involve that many malapropisms, since Alex rarely confuses words (except for a few gaffes, such as saying he feels “oblongated to eat” [26]). Really, the stilted language is a representation of over-the-top language use, committed more frequently by novice writers than foreign language learners. Still, the foreignness of Alex’s English does much to illuminate what we take for granted as native speakers, seen especially in the misunderstandings it generates. See, for instance, this exchange between Alex and Jonathan: “Do most young people have impressive cars in America? Lotus Esprit V8 Twin Turbos?” “Not really. I don’t. I have a real piece-of-shit Toyota.” “It is brown?” “No, it’s an expression.” “How can your car be an expression?” (71) See what he did there? First, Alex misunderstands the idiom “piece-of-shit,” then Jonathan responds with an ambiguous pronoun which Alex thinks refers to the car rather than the idiom “piece-of-shit.” The scene is comic, but it’s also instructive from a linguistic standpoint.

Foer’s representation of non-standard English, however, is not without its inconsistencies. Language, of course, does not function purely mechanistically, so we shouldn’t expect, for instance, that Alex will always substitute “manufacture” for make. But there are moments that feel forced, such as when Alex suddenly crosses out “understanded” and replaces it with the correct participle “understood” (157). This would be fine, except that it’s the only time such a cross-out occurs in his manuscripts. Similarly, Alex asks clarifying questions about his language use abruptly within an isolated paragraph late in the book: “It became dark—darker?—as we pursued her […]. We went past a miniature ocean—a lake?—and…” (183). Although Alex asks how to use words elsewhere in his writing, these flickering questions appear only in this paragraph, and for no particular reason, as if Foer decided, what the hell, in this paragraph he’ll start questioning individual words.

It’s moments like these that reveal a strain on part of the writer. He tries to add yet another formal quirk, to push his language yet another step forward, only to exhibit that such moves are superfluous, even showy.

“Look at Me”: Sentimentality and Pretension in the Fight Against Cleveritis

While Everything Is Illuminated does so much of interest structurally and linguistically, it strives too far to impress and emote throughout. Large stretches of the Jonathan narrative serve as a case in point. As previously mentioned, the chapter “Falling in Love, 1791-1803” and other similarly named sections overflow with emotional excess that doesn’t seem to do much more than toy with and tantalize readers. We are told, for example, that the foundling Brod was “a genius of sadness, immersing herself in it, separating its numerous strands, appreciated its subtle nuances. She was a prism through which sadness could be divided into its infinite spectrum” (78). Well, that’s a pretty metaphor and all, but is there any explanation for why Brod is sad? She doesn’t even know she’s an orphan. And an “infinite spectrum”—isn’t that a bit much?

Perhaps more perturbing than the heart-pricking turns, though, are the over-sexed liaisons that occur so frequently in Jonathan’s narrative, again for little to no purpose plot- or theme-wise. The famed Trachimbrod day, originally a moment of compelling indeterminacy in a story about the opacity of historical events (did Trachim fall into the river of didn’t he?), surges into a bonanza of sexed-up revelry in later chapters, as we are told that acts of fornication emit “a coital radiance that takes generations to pour like honey through the darkness of astronaut’s eyes” (95). Readers might find the introduction of the astronaut imagery a bit baffling, if not irrelevant—a sort of literary flourish that says, “Hey, I can jump between time periods and spatial settings seamlessly.” Next thing we know, Jonathan’s grandfather is getting sweaty with the sister of his bride-to-be—along with a host of other mistresses and lovers when he is as young as ten. The worst of these is probably the scene in the theatre, in which Foer suddenly breaks into a spree of narrative written like a play, a device likely taken straight from the Circe chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses. To make matters worse, the showy form tracks the grandfather’s effortless seduction of a gypsy girl, which climaxes just as the theatre band tops off their crescendo—a rather worn cliché.

Many of these pornographic stunts could be rubbed off as simple smut to please the crowds, that is, if they weren’t so formally pretentious to boot. Here’s where the axe comes crashing down for Foer’s prose: it yearns to strut its ingenuity and pass off old experimental hijinx as cutting edge while pandering to base sentiments. Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close ratchets such displays up a notch with its graphic representations, such as photos, marginalia, and blank pages, many of which are about as new as Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, published in … 1759. Indeed, Serpell writes that Foer’s second novel “borrows its formal verve and its emotional energy from the past.” Here, Serpell has the Modernists in mind. But while Joyce and Woolf add formal features that accomplished something unique—see the dreamy, slurred words of Finnegans Wake for an extreme example—Foer’s graphic “innovations” are largely superfluous in the points they make, leading Serpell to characterize them as “largely redundant” and “mechanistic rather than purposive.” Do we really need to see a picture of hands with “YES” and “NO” written on them right after they’ve been described?

Everything Is Illuminated is a less frequent perpetrator of such gimmicks. Yet, the sequence of encyclopedia entries near the novel’s end, capped off with a whole page-and-a-half of the repeated phrase “We are writing…” (212-13) pushes toward pretension or even “cleveritis.”

In David Foster Wallace’s interview with Larry McCaffery for a 1993 edition of The Review of Contemporary Fiction, the up-and-coming young writer introduced the term cleveritis with the following diagnosis:

cleveritis—you know, the dreaded grad-school syndrome of like “Watch me use seventeen different points of view in this scene of a guy eating a Saltine.” The real point of that shit is “Like me because I’m clever”—which of course is itself derived from commercial art’s axiom about audience-affection determining art’s value.

While I’m not one to question the intention’s of fiction writers, there are moments in Foer’s novels that edge closer to the “look at me” strain of experimental writing. What can said more certainly, though, is that Foer’s fiction, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close above all, has gained popularity largely because of “audience-affection.” A quick glance at Amazon.com book reviews will show how many reviews appreciated the waves of emotion the novel sent their way. According to Serpell, many of her students report crying at the end of the 9/11 bestseller when she teaches it. And then there’s my friend, gushing about the “one strange ocean of feeling” that Foer’s writing evokes.

Does such sentimentality devalue Foer’s works? Perhaps. The real drawback, though, comes from the way such overwrought moments distract from the formal and thematic concerns of the novel—its treatment of the reconstructed memory and the writing process. In my final section, I would like to interpret a closing passage of Everything Is Illuminated that bears witness to the seriousness of Foer as a writer despite the sentimental overtones.

A Polyphony of Voices and the Ghosts of the Holocaust

Alex’s narrative concludes with a chapter titled “Illumination,” a dramatic reveal toward which the story has been progressing ever since mentioning the import of what Alex’s grandfather did “during the war” (74). At this juncture, those wishing to avoid SPOILERS should read no further.

Effectively, the scene collapses into a ultra-Modernist stream-of-consciousness lacking punctuation and even spacing between words at times. The sequence of events is simple enough and even reiterates parts of an earlier Holocaust scene: Alex’s grandfather is rounded up along with the rest of his Ukrainian village, including his wife, newborn son, and timid Jewish friend Herschel. As the merciless Nazi officers force the citizens to identify the Jews among them, Alex’s grandfather is faced with risking his own life and that of his family or condemning his dearest friend to a horrific death. Relaying the impossibility of this circumstance decades latter, he struggles to explain: “a father is always responsible for his son and I am I and Iamresponsible not for Herschel but for my son because I held him with somuchforcethatIcried because I loved him so much that I madeloveimpossible and I am sorry […]” (252). At first, the compression and repetition of words seems to represent only the grandfather’s fear in that dire moment in 1941. However, the trembling voice belongs not just to the past, but to the present as well. This narrative, after all, has been transcribed by Alex, not his grandfather, after listening to his confession. So, at the very least, the trembling voice evokes the still-present-fear of a man lamenting an impossible choice. But Foer takes this shtick further.

In the subsequent effusion of words, Alex continues his transcription toward a universal culpability:

it is you who must forgive me he said these things to us and Jonathan where do we go now what do we do with what we know Grandfather said that I am I but this could not be true the truth is that I also pointedatHerschel and I also said heisaJew and I will tell you that you also pointedatHerschel and you also said heisaJew and more than that Grandfather also pointedatme and said heisaJew and you also pointedathim and said heisaJew and your grandmother and Little Igor and we all pointedateachother so what is it he should have done hewouldhavebeenafooltodoanythingelse but is it forgiveable what what he did canheeverbeforgiven for his finger for whathisfingerdid for whathepointed to and didnotpointto for whathetouchedinhislife and whathedidnottouch he is stillguilty I am I am Iam IamI? (252)

In a mode that blends form (stream-of-consciousness) and content (collective guilt) together, Alex’s description of his grandfather’s fear becomes his own fear, as he calls out to “Jonathan,” and the “I” that referred to his grandfather earlier shifts over to himself, for “the truth is that I also pointedatHerschel” and, indeed “you also pointedatHerschel.” Unlike the first passage I cited far above, the shift in pronouns is obviously purposeful, representing the universality of blame and condemnation for all those associated with the Holocaust’s atrocities, down through the generations. Maybe some of the run-together words speak to an excess here, and maybe the explosion of feeling on Alex’s parts comes off as exaggerated. But these are Alex’s feelings, rooted in his character, building off his grandfather’s experiences. His feelings actually make sense in the context and tie into the novel’s themes. But best of all, they don’t try to trick me into feeling anything. They don’t recite some tender, through threadbare, phrase or conjure up some impressive but unnecessary image.

If only more contemporary fiction could forego the cheap sex and literary parlor tricks for this kind of concentrated prose. That would be enough illumination for me.

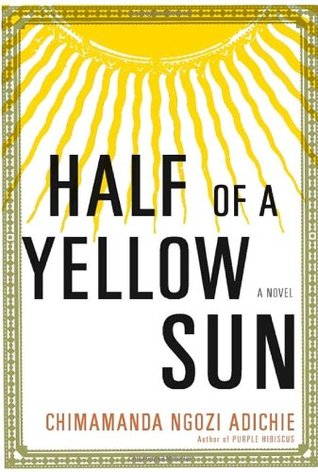

just as well known for her nonfiction as her fiction: her slim treatise We Should All Be Feminists (and accompanying

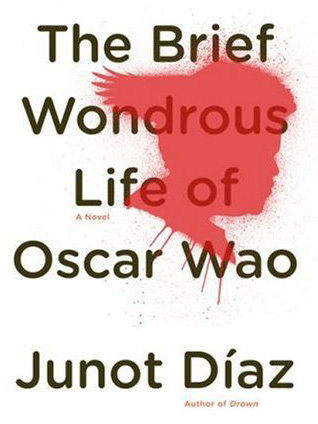

just as well known for her nonfiction as her fiction: her slim treatise We Should All Be Feminists (and accompanying  has written centers on Dominican or Dominican-American characters, often young men or boys chasing after women. He was asked about and directly acknowledged the close resemblance between him and his character Yunior, who narrates the novel The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and recurs in many of his short stories. But as with any fictional construction, Yunior is still disconnected from reality. D

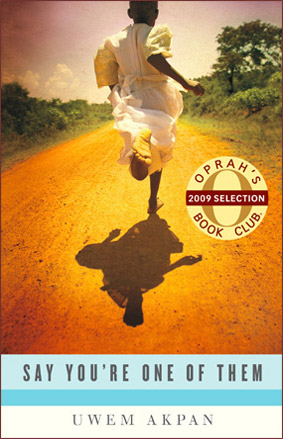

has written centers on Dominican or Dominican-American characters, often young men or boys chasing after women. He was asked about and directly acknowledged the close resemblance between him and his character Yunior, who narrates the novel The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and recurs in many of his short stories. But as with any fictional construction, Yunior is still disconnected from reality. D beyond Fr. Akpan’s purview. He writes from the perspective of an AIDS orphan, for example, an experience entirely foreign to him. Though he has been criticized for attempting to embody experiences beyond his own, he made what I found to be a very convincing defense of his fictional reaching. Don Cheadle, he noted, didn’t get any flack for playing the role of a Rwandan genocide survivor despite the absolute foreignness of that experience for him, so why should artists of other sorts be chastised for exploring experience not their own, provided they can do so convincingly? If you can only write about your own experience, he seemed to say, your art becomes bogged down in yourself and fails to identify and direct attention toward other moments of suffering and importance.

beyond Fr. Akpan’s purview. He writes from the perspective of an AIDS orphan, for example, an experience entirely foreign to him. Though he has been criticized for attempting to embody experiences beyond his own, he made what I found to be a very convincing defense of his fictional reaching. Don Cheadle, he noted, didn’t get any flack for playing the role of a Rwandan genocide survivor despite the absolute foreignness of that experience for him, so why should artists of other sorts be chastised for exploring experience not their own, provided they can do so convincingly? If you can only write about your own experience, he seemed to say, your art becomes bogged down in yourself and fails to identify and direct attention toward other moments of suffering and importance.